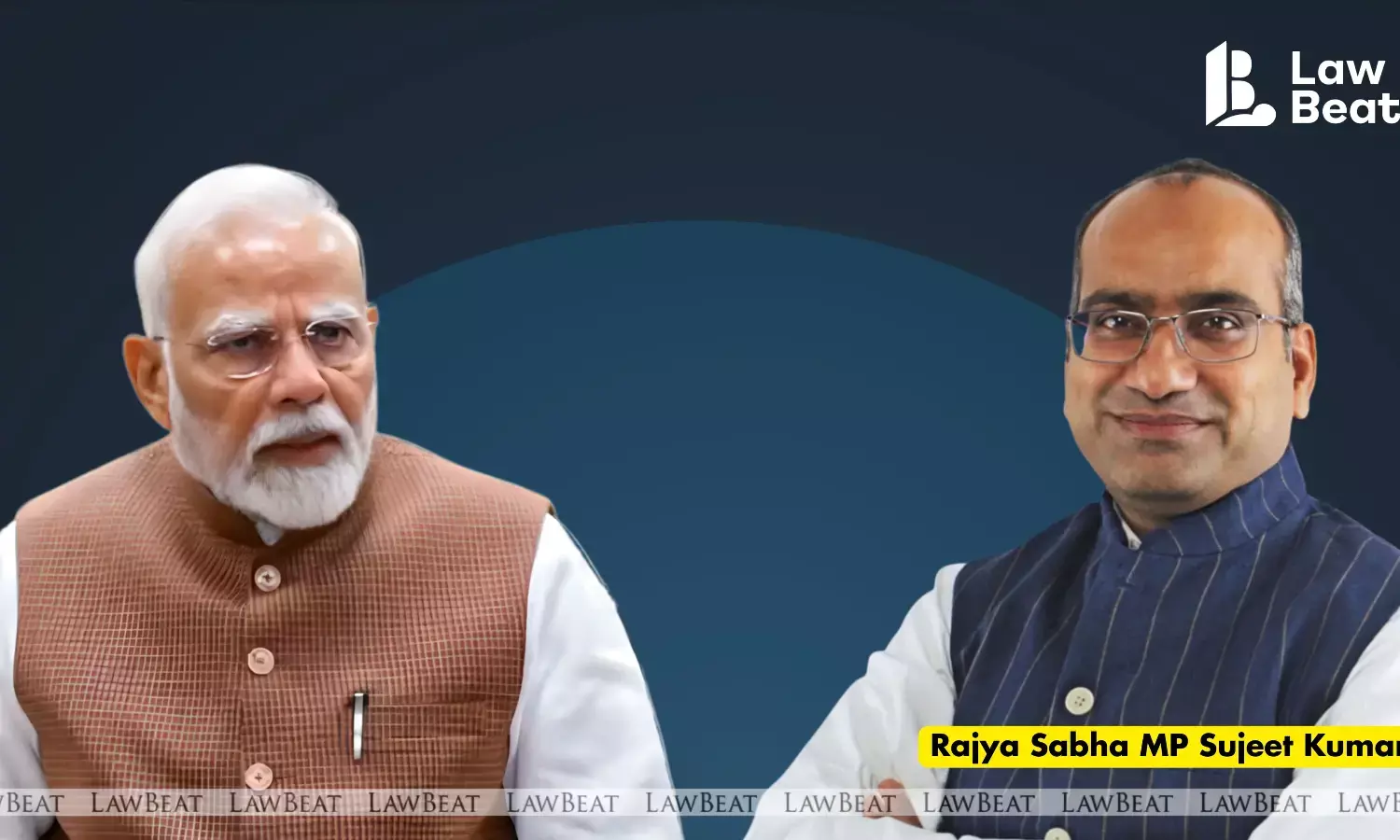

Rajya Sabha MP Sujeet Kumar Calls for Removing ‘Lord’ Prefix from Names of Former British Officials

Beyond Titles and Terminology, Sujeet Kumar’s Quiet Role in Shaping Modern Indian Law

The Prime Minister’s recent comment questioning the reverence historically shown to Macaulay has once again pushed the conversation on decolonisation into the centre of public debate.

Speaking in the context of India’s evolving educational landscape, the Prime Minister suggested that India must critically reassess the frameworks left behind by Macaulay, whose influence shaped the country’s schooling for more than a century.

His remark was interpreted as an invitation to revisit long standing habits, vocabulary and structures that were accepted unquestioningly for decades.

In this backdrop, Rajya Sabha MP Sujeet Kumar offered a pointed but measured observation. He suggested that India should remove the “Lord” prefix from the names of former British Governors and Viceroys in official usage.

The suggestion, simple in phrasing and devoid of political flourish, immediately resonated with ongoing discussions about how modern India should represent its past.

It came during a moment when several parts of the State are actively reviewing inherited colonial era practices, prompting many to see his remark as aligned with a broader national effort to reshape institutional language and memory.

MP Sujeet Kumar’s intervention fits neatly into the broader context of decolonisation that has come to define several recent policy choices.

Over the last few years, the present government has consistently directed attention to the symbolic and structural remnants of colonial rule. School curriculums are being revisited to include more material on indigenous knowledge systems, Indian civilisational history and local intellectual traditions. New pedagogical approaches increasingly emphasise Indian perspectives rather than inherited European narratives.

The move to overhaul the country’s criminal laws also formed part of this wider trend. The replacement of laws that had remained largely unchanged since the nineteenth century was presented as an attempt to shed legal structures originally designed for a colonial administration.

The shift towards new procedural codes and evidentiary frameworks was described by the government as a break from the mindset in which Indian citizens were governed as subjects rather than participants in a constitutional republic.

These steps, taken together, have created an atmosphere in which reassessing the language used to describe colonial figures no longer feels merely symbolic, but rather a natural extension of the country’s ongoing institutional self-reflection.

Judicial spaces too have not been untouched by this movement.

Several judges across the country have, in recent years, publicly expressed reservations about continuing colonial-era modes of address such as “my lord” or “your lordship.”

While some courts have allowed counsel to use alternatives like “sir,” “your honour” or “learned judge,” the larger sentiment within the judiciary is now moving towards an acknowledgement that such expressions no longer match the democratic ethos of the courtroom.

In this context, MP Sujeet Kumar’s comment appears neither isolated nor abrupt.

It reflects a growing awareness among lawmakers that the country’s official vocabulary often carries historical weight that must be reconsidered. His suggestion, made without dramatic positioning, asked a simple question: why should a sovereign nation continue to formally use titles that once signified authority over its people.

The fact that the question was raised during a period of active policy reform made it more than a passing remark. It became a reminder that even small linguistic habits can shape how a country remembers its past and imagines its future.

The idea of removing the “Lord” prefix also aligns with the broader cultural shifts visible across public institutions.

From renaming roads and public buildings to replacing insignia in military formations, there has been a conscious effort to reshape the visual and linguistic symbols of State.

MP Sujeet Kumar’s remark therefore fits into a wider continuum in which political leaders, judges, educators and administrators are actively questioning what India chooses to retain from its colonial past.

His suggestion adds to the growing catalogue of interventions urging the country to think more carefully about how it names, remembers and represents historical figures whose roles were closely tied to imperial governance.

At a time when the government has foregrounded decolonisation as a guiding theme in policy and cultural reform, his comment finds a natural place; It captures the quiet but persistent shift towards reframing the nation’s historical narrative in a manner that is both self assured and grounded in present-day constitutional values.